Interview with Pavlos Kozalidis

“I just love photography. It’s my obsession, my passion, the air that I breathe, the peace.”

Pavlos Kozalidis is a Greek photographer born in 1961 in Piraeus, who has dedicated over forty years of his life to exploring the world through the lens of his camera. A self-taught photographer, Kozalidis began taking pictures in the 1980s, traveling through India and Central Asia, and later documenting the lives of Greek communities around the Black Sea region. He has journeyed through more than 80 countries, creating an impressive body of work estimated at around 700.000 frames. He works exclusively with black-and-white film, and his photographs capture authentic moments of everyday life with a deeply humanistic sensitivity. He has exhibited rarely and only recently became active on social media — yet quickly gained recognition as one of the most talented, honest and devoted photographers of his generation.

In this interview, Pavlos Kozalidis speaks about his recent travels through Central Asia and the uncompromising life he has dedicated to photography — his therapy, his obsession, and the visceral force that keeps pushing him back on the road in search of ghosts. His words remind us that true artistic devotion lies not in achievement, but in honesty, persistence, and an enduring hunger for the unknown.

You can follow Pavlos Kozalidis on Instagram here: https://www.instagram.com/pavloskozalidis/

His most recent photo book, Searching for a Lost Homeland, signed by the author, is available by request via email: support@skiadopoulos.gr.

1. Your last journey followed the path of Alexander the Great. Why did you choose this subject, and what drew you to these specific countries? Had you been thinking about these destinations for a long time, and how does your interest in Alexander’s story shape the way you travel and photograph?

Some of the countries I had in mind, I already knew; others, I didn’t. I didn’t know Tajikistan — I knew its history, but that was all. The same goes for Uzbekistan. As for Afghanistan, this was my fourth time there: once when the Taliban were in control, in 2002; twice during the American presence; and now, in 2025.

The route more or less followed the path of Alexander the Great and his army, only this time, I picked it up from the Central Asia part of his journey. That’s what, for more than 30 years now, has really kept taking me back again and again to countries like Iran, Pakistan, India, Egypt, the Middle East, Palestine, and also parts of Greece, the Balkans, and Turkey.

I was already traveling to all these countries — Pakistan, in the early years, Afghanistan, Iran — and Alexander would always come up in conversations, especially after people found out I was Greek. They mentioned him with pride. Not like a god, but like someone truly important. After all these years, no one had anything bad to say about him. And I thought, well, this is interesting. So his journeys became my journeys. I was, in a way, looking for ghosts. That’s even one of the titles I thought of for a book — Looking for Ghosts. Another idea was Towards Macedonia — because, in the known world at the time, everywhere you turned was Macedonia. Go left — Macedonia. Right — Macedonia. North, South — Macedonia. And then there was A Child of a Dream, or Child of Dreams.

So yes, it’s this subject that drives me — but I photograph everything. I’m not just searching for the ghost of Alexander the Great. I capture everything I encounter along the way, in parallel with the story. Because when I arrive in a country, I don’t go there to photograph one thing — like the miners, or religion, or something specific. I photograph whatever draws me in — actually, not even what I find, but whatever I feel for. Because I need to feel it in order to photograph it.

2. How do you usually approach such extensive trips — do you follow a structured plan, or rely more on instinct? What were the main logistical challenges you faced in Central Asia, in terms of visas, access, or safety, and do you ever work with local guides?

I just let things unfold — it’s purely instinctual. It depends on how I feel about the place, about what I see, about my first impression. I usually know within the first hour whether I like a place or not — and the opposite is also true. Of course, there’s always some problem-solving involved, because issues inevitably come up. But overall, things usually work out fine. There were some difficulties getting the visa — mostly because these countries are still very paranoid. There were a lot of questions like: “Why you?”, “Why now?”, “Are you a journalist?” and so on. But eventually, I did manage to get the visa. I don’t use local guides — I don’t need them. In fact, most of the time, I travel without a guide. I don’t like having one. Accessing certain regions is generally quite easy if you have money and some degree of security, especially in Afghanistan. In Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, I didn’t need a guide — I just don’t like having one.

3. What struck you the most about these places?

What struck me the most — well, in Afghanistan, how much is still preserved and untouched. Not affected by tourism, not by curiosity, not by anything. Many of the forts and places of historical interest are basically still intact. In Tajikistan, I didn’t explore very deeply, but I believe I captured two or three photographs that help tell the story of the area Alexander visited. Still, there’s so much more work to be done — and I’ll be going back soon, very soon.

4. What’s the most important piece of advice you could give to a photographer considering a visit to those areas?

Great patience — that’s essential. You really need to be careful, because in places like Tajikistan, and even more so in Afghanistan, there’s no real infrastructure for tourism. You have to be good at problem-solving — especially in Afghanistan: how to get around, how to deal with the authorities. They have no experience dealing with foreigners. And again, especially in Afghanistan — it’s raw, it’s wild, it’s like the Wild West, which is wonderful, but it comes with its own set of challenges.

5. What nourishes you the most during such a journey — the act of photographing itself, encounters with people, the newness, the danger?

What nourishes me — what drives me — is the act of photographing. Photography is everything. The people, yes. The danger — not in a romantic sense; I don’t really think about it that way. You know, if there are photographs to take and a good story to tell, that in itself is the motivation — the fuel, the curiosity. The passion lies in the journey, in the photographing, and in the people you come across. As for danger — I don’t seek it out, but if I end up in a dangerous place (and I have, many times), I’m quite good at problem-solving and calming things down if a situation gets out of hand.

6. What exactly gives you the feeling of freedom when you set off on these adventures? It can’t be just about distancing yourself from familiar places and people.

The feeling of freedom, for me, comes simply from being out there and seeing new things. It’s the closest an adult can get to feeling like a child again. I think that’s why everyone loves traveling — it brings back that childlike curiosity. All your instincts — your sense of smell, sight, hearing — become heightened because you’re in a place you don’t know. Everything is on high alert. I think that only happens when you’re a kid discovering the world. So, for me, It’s the “new” that I truly love: new sounds, new food, new smells, new music, new people, new colors. Everything new. That’s what excites me.

7. How do you photograph in such isolated or tense places? Do you have a personal code? Do you talk to people first, or observe from a distance?

In a lot of the countries I go to — and I go to them again and again, not just once — I spend time observing people, especially their body language. In most cases, when I photograph people, they don’t know I’m photographing them. I’m quite stealthy — I walk, shoot, and move on. I don’t stand in front of them, I don’t coach them, I don’t tell them what to do. I don’t stage my photographs. Very rarely do I set up a shot. And even when I do have a connection, when I talk to someone before taking a photo, I let them compose themselves — because it’s their own dignity they’re offering you, and that’s something they should control, not me. So you have to be very, very fast — so they don’t even see you.

8. Have there been moments when you were afraid? Or did photography feel like a shield — a universal language?

Of course, there were many times — over these 40 years of traveling — when I was afraid. Sure. No, there’s no shield. If you’ve done something — or if they think you’ve done something, or even just suspect you — nothing protects you. You’re completely exposed, it’s open season for them to do whatever they want. Especially in the days before telephones, the internet, GPS… you were truly alone. It felt like being out in the middle of the Pacific in a small boat. You had to solve problems on your own. Nothing shields you out there.

9. You shoot exclusively on film. How do you manage your rolls, the risks, batteries — in areas where nothing is guaranteed?

Yes, I shoot exclusively on film. As for the rolls — yeah, it’s a real pain. X-ray machines are my worst, worst nightmare. And then there’s the fear of someone coming into my room and ripping off my bag — police, authorities, or just someone taking all my films and my gear. Has that happened? Yeah, a few times. Luckily, I was able to talk my way into getting my films and all things my back. Film comes with a lot of problems. But you know, you give something up, and you get something in return. And vice versa. I know I gain something from shooting film — beyond just the enjoyment. It’s very hard to shoot film today. And when it comes to equipment and batteries and all that, you carry everything on your back. I carry nothing under 25 kilos, plus another six or seven kilos of cameras. It really takes a toll on your body. But like I said — you get something, you give up something. You give up something, you get something.

10. Is there one image from this trip that you feel will stay with you for the rest of your life? Tell me about it.

Well, there’s more than just one — there are a few. You know, photographs are witnesses to your life. And there are some photos I’ve taken that I really love because I remember the exact seconds before I clicked the shutter — and the few seconds right after. They’re reminders of very, very good moments in my life — of the time I was there, that I saw it, that I photographed it. So yes, photography is a witness — a recording of your life, a journal.

11. Now that you're back, how is this journey settling within you? Are you the kind of person who can’t wait to look at the contact sheets, or do you savor the delay and let time distill the experience?

Now that I’m here, I just want go out there again and shoot more. I don’t even care about developing my film or anything like that. Obsessed, I am obsessed. I don’t know how to explain it, but I’m sure of one thing: a lot — I mean probably 80 percent — of the photographs I’ve taken, I’ll never actually see. The delay is interesting, you know, because it allows you to relive things. Let’s say I develop my film a year later — in that moment, I get to relive what I experienced a year before. But honestly, I just want to keep photographing. I can easily wait a year, even two, to see my work. I don’t mind. I’d rather just photograph. Photography is my therapy. It’s what quiets my mind — the only thing that does, not even drugs can do that. All the rest — developing, exhibiting, books — none of that really interests me. Otherwise, I would’ve made more than just one book. What I love is the act itself — being in the moment of photographing. Everything after the click doesn’t really matter to me.

12. Do you keep a travel journal — notes, fragments, ideas, encounters — or do you rely solely on memory and what remains in the photograph?

I have kept some journals, and I do write — and I know how to write — but I’m a photographer. I tell stories in a frame. Or rather, I take pictures that allow others to create their own stories when they look at them. So basically, the photograph is the journal. I do keep things that remind me of the trip and all that, but in the end, it all comes down to the photographs.

13. If photography is a way of life, the most important thing in the world, what does coming home mean to someone who loves to be on the road?

When I come back, it feels like death. The road trip is over — and it’s like fucking death. Everyday bullshit, life things — things you have to be around for, to deal with, to solve — for me, it’s just death when I stop photographing. Yes, I can start developing — but I hate developing. I always say this, I’ve been doing it for over 40 years. I’ve developed tens and tens of thousands of rolls. My body of work is close to 700,000 photographs — it’s a lot — and I hate the stupid darkroom. I hate the darkroom. I dislike everything else — even looking at my own photographs. Sure, it’s okay to glance back and see what I’ve done, but for me, the most important thing is being out there, photographing. Not showing, not organizing. And that’s probably one of the reasons why I didn’t show my work to Magnum — the two times I had the opportunity, once with Nikos Economopoulos and once with Costas Manos. I just didn’t want to organize it. I wasn’t ready to organize anything. I’m still not really ready. The only thing I want to do is photograph — not turn it into a problem. Photography is what makes me feel free. Organizing, books, exhibitions — all of that feels like chains. Heavy, heavy chains that steal your time from taking pictures. That’s what kills me.

14. What are your plans for the future? Where do you hope to go next? Is there a place you've carried in your mind for a long time but haven't yet reached?

The last project I'm working on — and the place I plan to return to after October — has to do with Alexander the Great and continuing his journey. I’ll probably end up going to Iran, Iraq, I need to return to Syria and Lebanon, and possibly Pakistan and Afghanistan. I’d like to believe I could do all of this in about four or five months, if I manage to find the time, because I really want to finish it.

Another book that’s just appeared over the horizon for me is Black Sea, Black Earth, which is about all the countries surrounding the Black Sea and their people. It runs parallel to the project I did with the Greeks of the Black Sea — I spent ten years photographing everything — so I have some work from that area as well.

A place I’d love to photograph — probably because it reminds me so much of the past — is North Korea, though it’s very difficult, since you can’t even bring film rolls into the country. For me, North Korea feels like time has stopped. All those posters, all that imagery I’m drawn to… I could photograph only people — no cars, everyone dressed the same. I think it would be the epitome of time standing still in a country, you know?

15. In a world increasingly driven by recognition and visibility, how do you keep your practice rooted in something real? How can you stay focused on the essence of your work?

Photography — like I’ve said — is therapy. It’s visual meditation. It quiets my mind. I’m a very emotional person. I feel everything around me. And sometimes it’s too much. But photography brings peace inside. That’s why I just want to keep photographing. Before Instagram, I used to tell myself people would discover my work after I died — and I was fine with that. I do enjoy the attention my work has received, but the best work comes when nobody knows who you are. That’s when you’re the hungriest. The more people know you, the lazier you get. You get corrupted, even by praise. You start to believe you’ve arrived somewhere. But in truth, you haven’t arrived anywhere. Because one must practice all their life — the one thing they truly love — and sacrifice everything for it. You have to stay on the road, no matter how hard it gets. You really need to go all the way, like Charles Bukowski says. That’s my favorite poem — “Go All the Way.” I’ve lived every word, every letter of that poem. And I still do. I just love photography. It’s my obsession, my passion. The air I breathe. The peace. The calm. And that’s it.

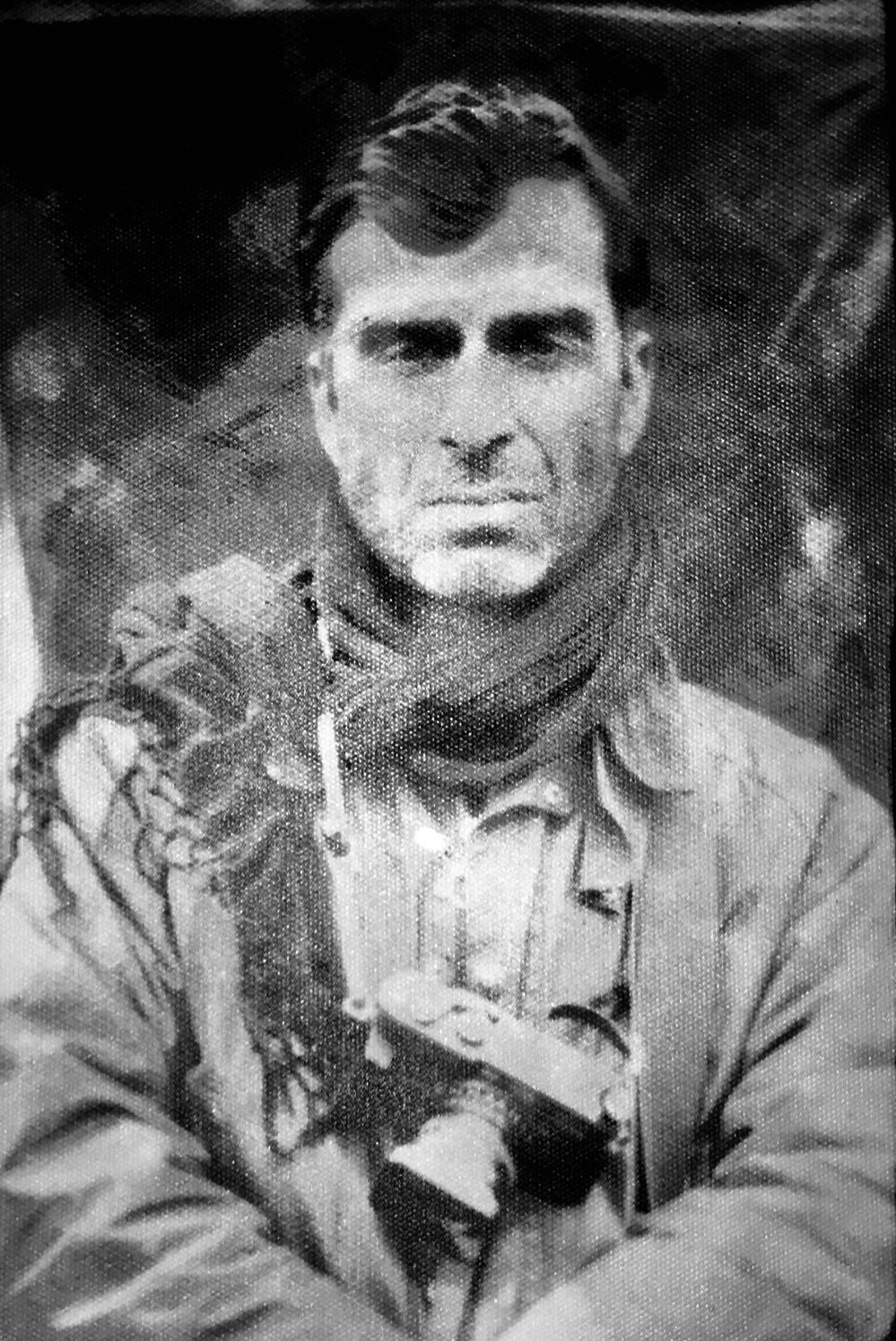

Pavlos Kozalidis on his first trip to Afghanistan (2002)